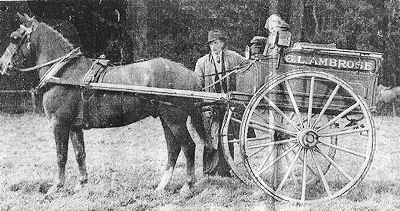

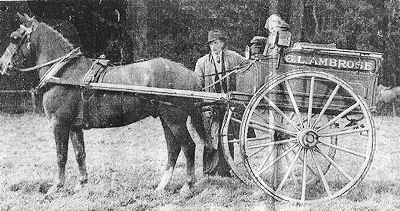

There was also deliveries across country by horse and cart made

by Harry. The photo shows Sandy the horse, Harry Goble and in the driving seat

Madeline Ambrose. One delivery round went up to one of the cottages on the

Stansted Estate, across farm tracks to homes in West Marden and returning via

Walderton. When on holiday I used to accompany him and on a few occasions was

allowed to make deliveries on my own. Another disaster occurred when making a

delivery to Woodmancote similar to one experienced by Harry elsewhere. I was

going up the hill from the old slaughterhouse when the back trap door opened

and deposited my delivery on the road. Fortunately the tray remained intact

keeping the orders from spilling out. The fun part for me was after returning

to the stables and taking off the harness. This was riding Sandy bare back to

the fields that were off the road to Aldsworth. Catching him again for another

delivery could be tricky. He could dash off as far a he could go or eventually

be tempted to take a meal of oats out of a bucket for a halter to be secured.

Then another bare-back ride to the stables.

The shop was only part of the Ambrose business, another

was the slaughterhouse at the bottom of his garden together with stables, tack

room and pig sties. He also had a couple of ferrets who enjoyed the occasional

chicken head. During the war and after when meat was rationed extras were

obtained by a group of villagers who formed a pig club. With the support of Mr

Ambrose the pigs were housed in sties that backed onto Ellesmere Orchard into

which the manure and straw was dumped to mature. Over several months the club

members collected swill comprising household scraps from friends and

neighbours. Each day the swill was mixed with water and cooked in a large steel

pot heated by a log fire. The timing was that the pigs were fattened for

Christmas when they were slaughtered. The picture shows the joints of pork

proudly displayed by Mr Ambrose, Mr Todd and other helpers. How the joints were

allocated to club members cannot be recalled. What is remembered is that our

regular favorite joint was a hind leg, and very good it was too. We were told

the only bit of the pig you couldn't eat was the squeak! The shop was only part of the Ambrose business, another

was the slaughterhouse at the bottom of his garden together with stables, tack

room and pig sties. He also had a couple of ferrets who enjoyed the occasional

chicken head. During the war and after when meat was rationed extras were

obtained by a group of villagers who formed a pig club. With the support of Mr

Ambrose the pigs were housed in sties that backed onto Ellesmere Orchard into

which the manure and straw was dumped to mature. Over several months the club

members collected swill comprising household scraps from friends and

neighbours. Each day the swill was mixed with water and cooked in a large steel

pot heated by a log fire. The timing was that the pigs were fattened for

Christmas when they were slaughtered. The picture shows the joints of pork

proudly displayed by Mr Ambrose, Mr Todd and other helpers. How the joints were

allocated to club members cannot be recalled. What is remembered is that our

regular favorite joint was a hind leg, and very good it was too. We were told

the only bit of the pig you couldn't eat was the squeak!

A few years

later when I became his errand boy my experience in the slaughterhouse began.

The team, if that is the right word, was Mr Ambrose the registered

slaughterman, a helper whose name cannot be recalled, Harry Goble and me. Most

of the animals slaughtered were pigs, although there was the occasional goat

from a private owner. The morning of the day for slaughter was started filling

the large coppers with water that was heated to boiling point. In the centre of

the slaughter room, shown above, was a very large domestic bath that was filled

with the boiling water. After a pig was killed its throat was cut and hung up

to drain out all the blood. It was then lifted into the bath and the hot water

softened the skin to allow the hair to be easily removed together with its

toenails. It was then hung up again and cut from throat to tail. It was my task

to collect the innards in my arms and transfer them to a bench for cleaning.

The tongue, lungs, heart and liver, called the pluck, was then removed all

connected and hung on a hook. My next task was to clean the contents from the

small intestine, called chitterlings, for making into a meal for the dinner

table. Meanwhile the pig carcase was hung on a rail and would stay there for

inspection and then for jointing in the shop. Some of the hind legs were salted

for a few weeks in a bath and then smoked in a kiln next to the

shop.

Before Christmas Mr Ambrose would visit the livestock shows and

buy one of the prize cows as a special treat for his customers. The dressed

carcass together with turkeys, geese and chickens were a major display in his

shop and attracted much admiration and visitors from afar. Christmas was a busy

time for me and Harry, who killed the birds, and we spent hours plucking them.

Towards the end of my employment Mr Ambrose started to branch out from

pigs to cattle. The first batch of about 15 cows arrived at Emsworth Railway

station. They were then walked from there to Westbourne by road. My task was go

ahead, warn traffic and ensure that gates were closed and guide the cattle past

side roads and other openings. A task that we all achieved successfully. For

whatever reason, I found the killing of cattle unsettling. Perhaps it was

because he had his own few cows that were used for milk and butter. I would

collect them from the fields where Sandy the horse grazed and return them

later. They had names and it can be understood how farmers get attached their

animals and are sad to see them eventually move on.

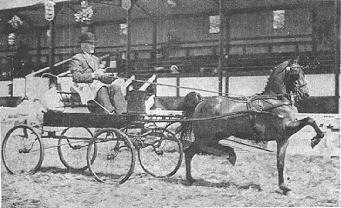

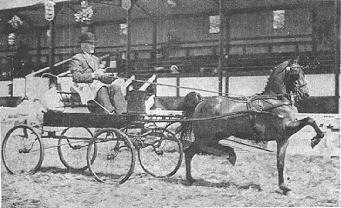

Apart from his business, the passion of Gilbert Ambrose

was hackney horses. In particular his first mare who is registered in the

Hackney Horse Society records as: 27501 Lady Westbourne - Breeder. Mr. G. L.

Ambrose. Westbourne. Emsworth. Foaled 1941 - Chestnut, blaze down face, white

off fore and near hind legs, white off hind coronet. The prefix lives on as in

2009 a Society member had a pony called Westbourne Whiz Kid. Apart from his business, the passion of Gilbert Ambrose

was hackney horses. In particular his first mare who is registered in the

Hackney Horse Society records as: 27501 Lady Westbourne - Breeder. Mr. G. L.

Ambrose. Westbourne. Emsworth. Foaled 1941 - Chestnut, blaze down face, white

off fore and near hind legs, white off hind coronet. The prefix lives on as in

2009 a Society member had a pony called Westbourne Whiz Kid.

Each year

Harry and I would spend several hours in the tack room polishing the buckles

and harness for a forthcoming show. The carriage was carefuuly washed with soap

and water and with chamois-leathered brought to a perfect shine. Beforehand,

apart from the training of the rhythmic canter, there were walks on the roads,

sometimes via Racton, to tone the muscles and increase stamina. On the days

leading up to a show Lady was groomed with a curry comb, washed, coat brushed

to a sheen, mane plaited and hooves polished. The photo is later in Gilbert's

career that featured on the cover of the prize schedule for the annual horse

show and flower show held at Romily Park, Barry, South Wales in August 1965. He

also had a pony for his children, Clifford and Madeline. As required, these

horses would visit Mr Goddard, the village blacksmith, for new shoes. If during

the winter months the roads were slippery Sandy would be fitted with special

shoes that had screw-in studs for extra grip.

His success with horses is

best summed up in words from his daughter Madeline: "He couldn't see a horse

without wanting to touch it. It was in his blood. He started his driving with a

little pony and trap; he graduated to shows and was soon touring the country

with his horsebox. Villagers would always take an interest, asking him where he

was off to as he hit the road for another show. His first horse was called Lady

Westbourne, and thereafter he gave all his horses the Westbourne prefix,

ensuring the name of the village travelled the country wherever he went. He

used to judge a lot. You could never keep him out of the ring. He was always in

there, always involved. The cups he had were just incredible. His horses were

always in physical perfection."

When I left secondary school in the

Summer of 1950 with no qualifications it was perhaps not surprising that I

began to work for Mr Ambrose full time. After a few months my father, who

worked in Portsmouth Dockyard, suggested that I should apply for an

apprenticeship. His advice was taken and somehow the examinations were passed.

I entered as a shipwright apprentice in January 1951 to begin a major change in

my life. |

The shop was only part of the Ambrose business, another

was the slaughterhouse at the bottom of his garden together with stables, tack

room and pig sties. He also had a couple of ferrets who enjoyed the occasional

chicken head. During the war and after when meat was rationed extras were

obtained by a group of villagers who formed a pig club. With the support of Mr

Ambrose the pigs were housed in sties that backed onto Ellesmere Orchard into

which the manure and straw was dumped to mature. Over several months the club

members collected swill comprising household scraps from friends and

neighbours. Each day the swill was mixed with water and cooked in a large steel

pot heated by a log fire. The timing was that the pigs were fattened for

Christmas when they were slaughtered. The picture shows the joints of pork

proudly displayed by Mr Ambrose, Mr Todd and other helpers. How the joints were

allocated to club members cannot be recalled. What is remembered is that our

regular favorite joint was a hind leg, and very good it was too. We were told

the only bit of the pig you couldn't eat was the squeak!

The shop was only part of the Ambrose business, another

was the slaughterhouse at the bottom of his garden together with stables, tack

room and pig sties. He also had a couple of ferrets who enjoyed the occasional

chicken head. During the war and after when meat was rationed extras were

obtained by a group of villagers who formed a pig club. With the support of Mr

Ambrose the pigs were housed in sties that backed onto Ellesmere Orchard into

which the manure and straw was dumped to mature. Over several months the club

members collected swill comprising household scraps from friends and

neighbours. Each day the swill was mixed with water and cooked in a large steel

pot heated by a log fire. The timing was that the pigs were fattened for

Christmas when they were slaughtered. The picture shows the joints of pork

proudly displayed by Mr Ambrose, Mr Todd and other helpers. How the joints were

allocated to club members cannot be recalled. What is remembered is that our

regular favorite joint was a hind leg, and very good it was too. We were told

the only bit of the pig you couldn't eat was the squeak!  Apart from his business, the passion of Gilbert Ambrose

was hackney horses. In particular his first mare who is registered in the

Hackney Horse Society records as: 27501 Lady Westbourne - Breeder. Mr. G. L.

Ambrose. Westbourne. Emsworth. Foaled 1941 - Chestnut, blaze down face, white

off fore and near hind legs, white off hind coronet. The prefix lives on as in

2009 a Society member had a pony called Westbourne Whiz Kid.

Apart from his business, the passion of Gilbert Ambrose

was hackney horses. In particular his first mare who is registered in the

Hackney Horse Society records as: 27501 Lady Westbourne - Breeder. Mr. G. L.

Ambrose. Westbourne. Emsworth. Foaled 1941 - Chestnut, blaze down face, white

off fore and near hind legs, white off hind coronet. The prefix lives on as in

2009 a Society member had a pony called Westbourne Whiz Kid.